The first weekend of February was one of the weekends that started off frustrating and disappointing and then somehow redeemed itself in a big way. I had registered to attend the Indiana Wildlife Federation 2024 conference. The focus was on Indiana waterways, and I looked forward to learning a lot and connecting with fellow greenies. However, I had to cancel. Then I thought, well, it is World Wetlands Day, why not attend the wetland hike at Eagle Marsh. Again, because of a sore knee, I had to stay home. While pouting I navigated social media and discovered that Notch Hostel in the White Mountains of New Hampshire had a fireside chat series. For those of us not staying at the hostel we could attend virtually. The disappointing weekend began to brighten up. Notch Hostel has an active Social Justice approach to hiking and engaging nature. This includes being inclusive to people of color, women, people with ability challenges, Indigenous Peoples, and members of the LGBTQ+ community. This inclusive approach is consistent with the values of this blog. If we are to address climate change in any effective way it will take all of us. If we are not to be discouraged from such a formidable challenge, we need the grounding and healing that comes from being in nature. That involvement in nature must be for all of us. The fireside chat represented one of the communities often excluded or at least not consistently warmly welcomed into the green and hiking communities, the trans community. The talk was on Queering the Triple Crown. The speaker, Lyla “Sugar” Harrod is the first openly trans woman who has completed thru hiking the three national trails that make up the Triple Crown. That includes the Appalachian Trail, the Pacific Crest Trail, and the Continental Divide Trail. She had hiked over 2500 miles. Her presentation was engaging, her insights useful, and her example was inspiring. She provided practicle advise for hiking while out and freely referred to the wisdom of others. Now this is not the first time this blog has addressed LGBTQ issues and contributions to the larger Green Community. In LGBTQI-A and Being Green the blog addressed issues of safety, belonging, career opportunities of LGBTQ folks in a variety of green settings. This included hiking, conservation, gardens, and farming. It identified resources for members of the LGBTQ community. However, the focus was on the larger, umbrella community (LGBTQ) and a broader sense of what is involved in being green. Lyla usefully narrowed the focus to the Trans community and the hiking community. Lyla began her fireside chat addressing the larger context. She addressed what is queering or what does it mean to queer something. This action, this verb, referred to the act of challenging traditional norms or assumptions about gender, orientation, and identity. It requires a questioning of traditional hierarchal relationships and of gender expectations. Interestingly, she pointed out that many in the hiking community already question traditional norms. She stated that thru hikers are dismantling conventional wisdom by “blowing up their lives.” She was referring to rejecting traditional career paths and conventional relationships. Lyla was inspiring. Her story is of a person who struggled with addiction and found her sobriety and her identity. She sees out-hiking as being a model to other members of the LGBTQ community who struggle to accept themselves or to outwardly be themselves. Lyla is an active member of a mentoring program for LGBTQ hikers. Lyla’s chat and the Notch Hostel’s core values got me thinking about the growing commitment to inclusivity in the green movement. Hiking is still very much a White CIS male environment but that is changing. It is being challenged by POC, by female accomplishments and leadership, but also buy the growing LGBTQ identity in hiking. This PRIDE is important. Just as important as the organizing is the fact that Queer eco-activism is being studied. Tere is growing advocacy for LGBT involvement in conservation and eco-activism. This includes the League of Conservation Voters, The National Wildlife Federation (including a focus on youth), and The Butterfly Conservation Organization. Even the United States Department of Agriculture is providing resources. So, I did not get to go the IWF conference. I did not go on a World Wetlands Day hike. But I did learn about the challenges faced by trans hikers. I was reminded of the many contributions of the LGBTQ community to the green movement. I was introduced to the many services and welcoming people that make up the Notch Hostel. And as far as the conference I missed, it turns out I can watch all the presentations on-line. Illustration by Kerri Pulley

1 Comment

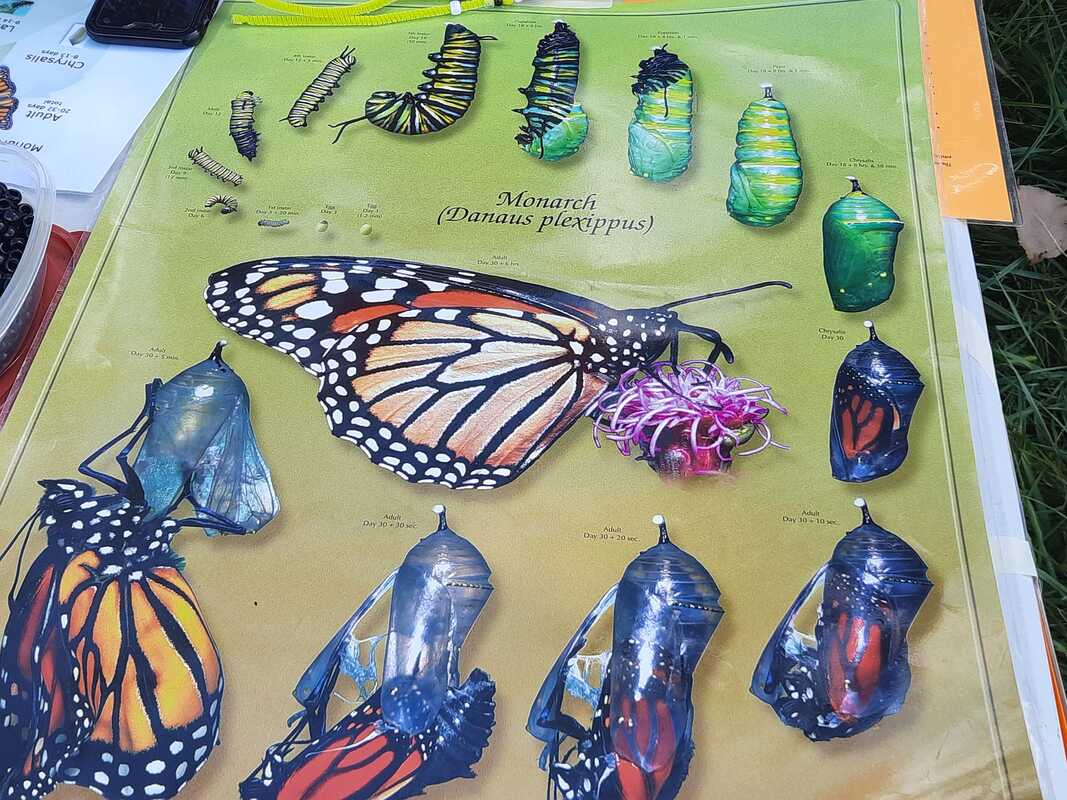

I first made rain barrels, in downtown Fort Wayne, at a workshop near the St. Josph River. The workshop was sponsored by the Tri-State Watershed Alliance which is now the Maumee Watershed Alliance. Because of that very positive experience I was excited when I discovered the Maumee Watershed Alliance was sponsoring another workshop at ACRES Land Trust headquarters. I invited my great-great niece, Zoe Clay, who is also a greenie, to join me. I then called the Alliance and received permission to record the workshop. First, the setting was wonderful. The workshop took place in a historic barn that was a hundred years old. I knew ACRES restored land; I did not know that on occasions they also preserve significant structures associated with the land. So here we were, at the first ACRES preserve near Cedar Creek and just a short drive from Bicentennial Woods. The presenters were Sharon Partridge of the Maumee Watershed Alliance and Kyle Quandt from the St. Joseph Watershed Initiative. They pointed out that watersheds provide water to agriculture, industry, homes, and nature in Northeast Indiana. I was grateful that they used a used a map during their presentation to illustrate the watershed from Michigan, Ohio, and Indiana that served the area. They then discussed the many contaminants and challenges the watershed faced. This included pesticides and fertilizers from agriculture, chemical pollutants from industry and urban areas, and poor water management. They also described the systemic way these issues were being addressed. The systemic approaches involved legislators, policy, technology, and short and long-term plans. However, there was a way individual citizens could help care for the health of our waterways and watershed, rain barrels. Water barrels reduce the amount of excessive water put into flooding streams and rivers. They also provide free water for gardens. After the lecture the participants were guided in making the rain barrels. Participants worked in teams of two to assist one another. Consistent with the value of contributing to the community, Zoe made her rain barrel for her grandmother. To celebrate such a green morning Zoe and I took a short hike in the Bicentennial Woods. We then finished the day by having lunch at an establishment that provides tasty and sustainable food, the Loving Café.  Once a month Little River Wetlands Project hosts a community forum, Breakfast on the Marsh. It is usually held at Indiana Wesleyan University Fort Wayne. The forum has guest speakers who address projects, land and/or water sites or issues related to nature. In November 2023 Amy Silva, Executive Director of LRWP introduced Philip Anderson. Mr. Anderson addressed the many competing demands placed on watersheds. Mr. Anderson was interactive with the audience. He engaged them regularly. He described himself as a teacher, a traveler, and a (story) teller. These three core characteristics guided his view of the many uses of water. Mr. Anderson identified multiple constituents who made demand of water use. These included farmers, developers, cities, industry, and nature. He asked us to identify where we use water and where does that water come from. This increased a sense of interconnectedness. He also stressed that while there are different perspectives on the use of water, we are best served by trying to look beyond our own perspective. He introduced the audience to multiple watersheds, locally, regionally, and internationally. For the LRWP audience that included Northeast Indiana, Michigan, Ohio, the Great lakes, and Canada. Locally that included the St. Jospeh Watershed, the Maumee Watershed, and the Auglaize Watershed. Challenges to the health of watersheds included agricultural contamination in the form of fertilizers and pesticides, urban pollutants, and climate change. He pointed out that our leaders and communities address these issues in terms of places (geography), uses, and policy. That leads to a collision of perspectives or a convergence. To increase the chances of convergence and collaboration he lead the audience in some problem-solving exercises. It was this focus on process that kept a knowledgeable audience engaged. As wetland protections are eroding these skills may prove helpful.  Little River Wetlands Project is involved in collecting information about Butterflies, Monarchs, and Moths. After months of collection and assessing the health of the environment and the bio-populations it is time to celebrate. LRWP sponsors Monarch Festival. This is a huge festival that thousands of citizens of Northeast Indiana participate in. The festival has art events, food trucks, educational events for children. There are art and craft booths all associated with Monarchs. However, the highlight of the festival is naturalist Jeff Ormiston demonstrated the tagging, recording, and releasing for fully developed Monarch Butterflies. Jeff used the protocols provided by Monarch Watch provided by the University of Kansas. Once released the butterfly begins the migration to Mexico. This is a migration that takes four generations to complete. It is a day of children playing and learning, artists creating, art, food, literature, and joy, all focused on Monarchs. As you watch this last video be sure to watch for the tagging and release of the butterflies.  Lepidoptera include moths and butterflies. Moth species are by far the most numerous. We tend to focus on butterflies because for the most part they are the most colorful and are seen during the day. However, as we were about to learn, rules, definitions, and characteristics about moths and butterflies were rarely absolute. The Moth Event at LRWP, like the Beaver Hike, was special. These are both events open to the public that take place at night. The lecture was at the Eagle Marsh barn. That was followed by a night time hike on marsh trails observing moth. Alyson Munger provided the lecture and guided the activities. An agency associated with monitoring moth populations is The National Moth Recording Scheme by the Butterfly Conservation agency.  Butterfly monitoring and Monarch monitoring are two different activities. What can be observed and counted differ. The environment differs In Monarch Monitoring. You also identifying milkweed (type and number) and you look under each leaf from top to bottom. You are looking for Monarch pupa, chrysalis, they are often in nearby trees. You are looking for stages of development and you are looking for feeding Monarchs. You are also identifying insects that may harm the health of milkweed. One of the agencies that provides guidelines for the projects is the Integrated Monarch Monitoring Program. The University of Minnesota was the reporting agency. The training includes learning the protocols, being able to identify milkweed, demonstrating observation-skills, recording, and reporting findings. There are numerous trails to choose from on all of the LRWP sites. The trainers for 2023 were Kathleen Silliman and Jenny Ratzlaff.  Many naturalists, nature-lovers, and community volunteers participate in Citizen Science projects. Citizen Science is a way to expand research, data collection, and measure changes that is cost effective and efficient. The experimental design and standardized protocols are created by the professions and then the participating citizens are trained on following the guidelines and submitting data. Most nature preserves, land trust, and nature sanctuaries as well as nature agencies participate in Citizen Science projects. I spend a considerable amount of my volunteer time with Little Rivers Wetland Projects. LRWP participates in projects focused on birds and nests, native plants, turtles, bats, invasive species, small mammals and butterflies and moths. Each project has it’s own university or agency that develops and directs the project. These include Purdue University, Georgetown University, and the Cornell Lab of Ornithology and other institutes. The next four posts will focus on Citizen Science projects focused on butterflies and moths or Lepidoptera. The three projects, Butterflies, Monarch Butterflies, and Moths have specific protocol for observation and recording data. The training courses differ, and the reporting agencies are different. The final post is a celebration of all of the volunteer efforts, Monarch Fest. During the last post the community is presented with the banding, recording, and release of Monarchs as they begin their migration to Mexico. Butterflies and Moths might be tiny compared to deer, eagle, and beaver but they are important. They provide food for other animals. They are also pollinators. Broadly speaking, butterflies are day-time pollinators and moths are night-time pollinators. They are monitored to estimate the health of their populations and the overall health of the targeted environment. If you are a Butterfly Monitoring volunteer, then walking through the marsh with your binoculars and clip boards is exciting. However, before you step out onto the trail you need to complete your training. owever, before you get to that point you must be trained. This is a specific gtraining that requires going though a manual, understanding the guidelines, and learning how to record your findings. This differs from the protocols for the Monarch Monitoring. This is a focus on all butterflies.The training is from the Michigan Butterfly Network and Georgetown University. Volunteers may also reverence the North American Butterfly Network. For the 2023 season the trainer was Russ Voorhees. Russ trains for LRWP but is also active in multiple projects and agencies. He is a retired educator and an important community asset.  I had planned on writing about the growing importance of indigenous wisdom and knowledge to the green movement. I wanted to do this in November because that is National Native American Heritage Month. However, most of 2023 has provided me with trainings and events about indigenous peoples and reflected a reality, every month is Indigenous Peoples month. So, I will begin 2024 reviewing some of the contacts, events, and trainings that I have participated in that highlight this growing influence on the green movement. This is not the first time I have addressed the influence of indigenous peoples and knowledge on the green movement. In August of 2022 I wrote about the influence of Indigenous Peoples. In December of the same year, I wrote about the land and history of the Algonquin of Ontario. As agriculture struggles to become more sustainable, healthier, and accessible to underserved communities I also wrote about Slow Food USA and Indigenous food programs. This includes traditional foods and diets, use of the land, and developing food distribution systems. Locally, in Northeast Indiana, there is still much to be learned from the original inhabitants of the land. Their names, memory, and impact are felt throughout the area. The Miami of Indian are active. They host Miami Days at Chief Richardville House. The convene across from the Seven Pillars Nature Preserve in Peru Indiana. This was a significant gathering place for many of the First Nations of the area. The Potawatomi Chief Metea is remembered for his skill as a warrior and an orator. Metea County Park is named after him, and Potawatomi camps are held at the park in the summer. Chief Blue Jacket is remembered by an agency that serves people requiring vocational retraining. A statue was dedicated to him, and his relatives visited Fort Wayne and attended the dedication. This Shawnee chief is remembered for his willingness to fight and to ally with other first Nations. This included joining forces with Chief Little Turtle of Miami for the Battle of the Wabash. Chief Blue jacket is also remembered locally with a coffee house that highlights American Indian art and bears his nickname, Tall Rabbit. A few miles from the coffee house is the memorial to his Miami colleague, Little Turtle. Nearby, at the Allen County Courthouse is a bust of Tecumseh. The Miami are active in educating the public about the history and the current life of Miami in the area. They do this through Miami Days, training Indiana Master Naturalists, and in public lectures. This highlights another truth, all lands on Turtle Island are Native lands. It reminds local communities that we do not need to go out West to experience Indigenous culture and life. Indigenous peoples are important to the green movement because of the knowledge they hold. Today we look at cornerstone species, species that sustain an environment and make it grow. They look at the same species as brothers and sisters and know you cannot eradicate them and not expect environmental consequences. So, the classes I took on beaver, bison, wolves, and eagle are classes on cornerstone species and brothers and sisters. Today bison are changing the face of the prairies and restoring their health. Beavers are restoring wetlands, fisheries, and protecting land against wildfires. Eagle sightings, once rare, and now almost common. They remind us to look at other species that are on the brink of extinction. Around the world indigenous peoples are the protectors of biodiversity, I take free one-hour courses through the Outdoor Learning Store. These courses are about using nature to engage children in learning. Many of the courses are taught by First Nation educators. Through the Outdoor Learning Store, I have also enrolled in the First Nations University of Canada. I am taking the Four Seasons of Reconciliation program. While the focus is on the relationship between First Nations and colonizers the use and misuse of land is part of this history. I have also attended virtual lectures sponsored by the Mamidosewn Centre which is part of the Algonquin College. The services and meditations are earth, sky, air, water centered. Foundational to learning about the impact of indigenous Peoples on protecting the environment was a program through Yale University and Coursera. The program, Religions and Ecology: Restoring the Earth Community consisted of five courses. These were: Introduction to Religion and Ecology, Indigenous Religions and Ecology, South Asian Religions and Ecology, East Asian Religions and Ecology, and Western Religions and Ecology. The Course on Indigenous Religions addressed the relationship between nature and peoples. There were examples of governments giving rights to rivers, indigenous people fighting to protect ecosystems, and the sacredness of place. Another forum that focused on Indigenous Peoples and ecology was the Parliament of the World’s Religions. I attended the 2023 Parliament in Chicago. I met Indigenous people from the Amazon, from around the world, and especially from Turtle Island. The United Nations had sponsored a special Amazon Summit to stress the pressing need to support restoration of the basin or the “lungs of the earth.” The speakers were from various Amazon basin countries and there were virtual government ministers who addressed us. I met Great Grandmother Mary Lyons who is one of the acknowledged wisdom teachers. I also interviewed the Indigenous Task Force chair, Lewis Cardinal. The interviews will be shared in future posts. In October and November, I attended a number of events that highlighted Native American/Indigenous Peoples’ Month. This included the Celebrate Indigenous and Native American Heritage Month with Flip!. I also attended, virtually, Celebrate Indigenous Peoples’ Day with Native American Dance and Storytelling sponsored by Allen Public Library, Allen Texas. The focus was on Choctaw and Chickasaw peoples. Finally, I attended Indigenous Peoples’ Day Community Celebration at Eiteljorg Museum in Indianapolis. The even included tours of the museum with emphasis on the relationship of First Nations with their environment, bison burgers, storytelling, and dance. Al of this is to say one month can not possibly convey the history, present day challenges, and pride of the Indigenous Peoples of Turtle Island. For that reason, this blog will address events, speakers, and issues in detail in 2024.  I have become fascinated by the important role animal sanctuaries play in the green movement. I was first attracted to wild sanctuaries that protected wild and endangered species. I visited a sanctuary for orangutans in Malaysia in 2012, the Semeneggoh Wildlife Center in Sarawak. I have friends who have visited elephant sanctuaries. This included an Elephant Jungle Sanctuary in Chang Mai Thailand and recently, the Udawalawe Orphan Elephant Sanctuary in Sri Lanka. I was a docent at Lincoln Park Zoo in Chicago in the 1980s, so these experiences were important to me. One of my goals for 2024 is to visit and interview staff at local farms that are green oriented. This includes Rick Ritter’s Fruit Growers Club and Dick's Organics. Rachel Neuhaus-McConville’s Knotty Pine Homestead. Rachel’s homestead is not a sanctuary but she provides her animals with stimulating and loving environments As she stays, "they have a good life and one bad day.” She is also a wildlife rehabilitation specialist. I especially want to visit Beth Conways and Tony Jeffers’ Corrymela Farm and Horse Boarding. Beth has been involved in all things green for a long time. She has also cared about the welfare of animals. She was a mayoral appointee to the Humane Education Advisory Council for Fort Wayne Animal Care and Control. The council helped produce the K.I.N.D (Kids in Defense of Nature) Club Show that was used in local schools to teach empathy. It was Beth who first introduced me to Jessica Wallace and her Lopin’ Along at the Micro Sanctuary. The Micro Sanctuary is a small sanctuary (four acres) located in a small town, Larwill Indiana. The sanctuary was founded in 2021. It has a few buildings and land that includes open field and wooded areas. Her focus is on providing a safe, peaceful life to rescued farm animals. At the time of my last visit the sanctuary was home to 45 animals. These included horses, goats, chickens, cats and a dog. Many of the animals were special need animals. So wheelchairs, special medications, and special housing were part of the environment. Jessica is not new to caring for animals. She earned an AAS in Equine Science and was a veterinary technician for 5 years. She lived in and around Cody Wy and Powell, Wy and went to college in Powel. She earned her animal caring credentials by spending two years on a dude ranch outside of Cody. Consistent with her empathy for animals, she was a vegetarian for six years and a vegan for the past four years. Jessica often collaborates with the Sassy Vegan. The sanctuary has a volunteer program, an active board, community support and a community profile. I visited the micro sanctuary twice. Once in the summer and had a leisurely tour of the programs and animals. The second time was an intimate Compassionate Feast, a post-Thanksgiving meal that was vegan as we ate and learned about the animals and programs. I hope to visit and interview workers at many animal-focused farms and sanctuaries in 2024. Sanctuaries protect endangered animals. They provide homes for wild animals that never should have been in captivity, locally that includes Black Pine Animal Sanctuary. In northeast Indiana there are several parks that focus on bison and elk. These include Wild Winds Buffalo Preserve, L.C. Nature Park, and Ouabache State Park. There are demonstration farms, educational homesteads that I hope to visit. However, I especially hope to return to The Micro Sanctuary. Jessica Wallace, her volunteers, and the animals have a lot of stories to share.  LC Nature Park is a cornerstone nature organization in Northeast Indiana. It is a farm that has restored much of its land to pre-settlement status. That includes wetlands, prairie, grassland, and a dune. It has also established a herd of elk and a herd of bison, animals that are indigenous to the area. The education center is a beautifully restored and highly functional barn. The park partially supports itself by hosting social and educational events. One of those events was Coffee and Calves. The presenters were from Utopian Coffee. This is a company that is involved in the whole journey of the coffee bean, from planting to drinking. Participants met in the beautiful education center with a pillar of elk antlers and a mounted bison head. The participants enjoyed baked goods and delicious and aromatic coffee while learning about the production of coffee and the challenges of a monocrop or plantation crop becoming sustainable. The journey starts with planting, growing, and harvesting. Then transportation and finally a variety of methods of roasting. By the time we had taken our sip of coffee the beans had been handled by fourteen different people. After the presentation we all took a short hike. Our goal was to spot elk and bison calves. These were two very different animals with different behaviors. Elk can grow to 700 pounds and the males sport antlers for half the year. Still, to protect the calves they hide in the woodland. We saw a few adults and that was enough to make us smile. Bison males can weigh up to 2000 pounds and both males and females have horns. They do not hide, the were out in the field. It was gratifying to see both species living in the Little River Valley. Prior to settlement there were up to 60 million bison in North America. By 1884 that number had dwindled to 325. These animals that were so important to the health of the prairies and plains are precious. Prior to settlement the elk population was estimated to be around ten million. Everything about this event was inspiring. We learned about coffee production and the challenge of growing coffee responsibly during climate change. We got to appreciate some of the five miles of trails in the park and appreciate the plant life. The herds were breathtaking. So, if you’re looking for events with pie, learning, and reason to hope, check out LC Nature Park. |

Archives

April 2024

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed